Implement a simple shift cipher like Caesar and a more secure substitution cipher.

"If he had anything confidential to say, he wrote it in cipher, that is, by so changing the order of the letters of the alphabet, that not a word could be made out. If anyone wishes to decipher these, and get at their meaning, he must substitute the fourth letter of the alphabet, namely D, for A, and so with the others." —Suetonius, Life of Julius Caesar

Ciphers are very straight-forward algorithms that allow us to render text less readable while still allowing easy deciphering. They are vulnerable to many forms of cryptanalysis, but Caesar was lucky that his enemies were not cryptanalysts.

The Caesar cipher was used for some messages from Julius Caesar that were sent afield. Now Caesar knew that the cipher wasn't very good, but he had one ally in that respect: almost nobody could read well. So even being a couple letters off was sufficient so that people couldn't recognize the few words that they did know.

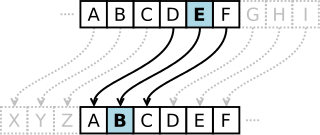

Your task is to create a simple shift cipher like the Caesar cipher. This image is a great example of the Caesar cipher:

For example:

Giving "iamapandabear" as input to the encode function returns the cipher "ldpdsdqgdehdu". Obscure enough to keep our message secret in transit.

When "ldpdsdqgdehdu" is put into the decode function it would return the original "iamapandabear" letting your friend read your original message.

Shift ciphers quickly cease to be useful when the opposition commander figures them out. So instead, let's try using a substitution cipher. Try amending the code to allow us to specify a key and use that for the shift distance.

Here's an example:

Given the key "aaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaa", encoding the string "iamapandabear" would return the original "iamapandabear".

Given the key "ddddddddddddddddd", encoding our string "iamapandabear" would return the obscured "ldpdsdqgdehdu"

In the example above, we've set a = 0 for the key value. So when the plaintext is added to the key, we end up with the same message coming out. So "aaaa" is not an ideal key. But if we set the key to "dddd", we would get the same thing as the Caesar cipher.

The weakest link in any cipher is the human being. Let's make your substitution cipher a little more fault tolerant by providing a source of randomness and ensuring that the key contains only lowercase letters.

If someone doesn't submit a key at all, generate a truly random key of at least 100 lowercase characters in length.

Shift ciphers work by making the text slightly odd, but are vulnerable to frequency analysis. Substitution ciphers help that, but are still very vulnerable when the key is short or if spaces are preserved. Later on you'll see one solution to this problem in the exercise "crypto-square".

If you want to go farther in this field, the questions begin to be about how we can exchange keys in a secure way. Take a look at Diffie-Hellman on Wikipedia for one of the first implementations of this scheme.

Sign up to Exercism to learn and master Perl with 5 concepts, 83 exercises, and real human mentoring, all for free.